Economists study things and make theories, and based on what they say, lawmakers set policy. That’s just one of the things that makes the world go round, and we don’t think about it too terribly much, or at least I didn’t, until I started seeing the phrase “human capital,” but now that I have, I pay attention. And I come up onto statements like this:

While such policies may increase the size of the next generation, their impact on the generation’s total human capital are unclear, since per person human capital may change as well. . . . This paper explores a potential national policy tradeoff, embodied in motherhood timing, between the quantity and quality of children.

This excerpt is from the article “Motherhood Delay and the Human Capital of the Next Generation” by Amalia R. Miller, American Economic Review, 2009. It looks at whether standardized test scores, an indicator of the future economic value of children (a.k.a. “human capital”), are affected by whether or not mothers delay childbearing. The answer to this question is intended to help countries decide whether or not to set “pro-natalist policies” — that is, policies that encourage women to have lots and lots of babies.

(A quick note on human capital, if you’ve never heard the term: it is the set of skills, education, and expertise of a worker or a labor force. Sometimes the term is used to refer to something the worker owns, and other times it means an asset a company owns, or a nation.)

I should mention I’m pretty creeped out by now. First off, I thought my kids were, well, children, not wealth. Next up, it’s disturbing that legislation surrounding childbearing should be affected by the wealth a nation is expected to reap from the children’s future labor. It means that human capital considerations could affect anything from anti-abortion legislation, if a nation is perceived to be running out of human capital, to forced sterilization, if the cost of raising a child is perceived to be higher than the human capital reaped.

But there’s one more thing that stands out when I look at articles regarding mothering and human capital. The unpaid labor mothers do, when we are perceived to be “not working,” has economic value to somebody outside our family, and people in power have measured that value. That’s interesting.

The United Nations is conducting a study called the “Inclusive Wealth Project.” There’s a 2012 report and a 2014 report. It is about the development of a new measure of the wealth of nations, on par with the gross development product (GDP) and human development index (HDI). The new “Inclusive Wealth Index” includes natural resources, produced resources, and human capital.

Here’s a taste of the math, from page 30 of the 2012 report:

Wealth = Pmc * Manufactured Capital (MC) + Phc * Human Capital (HC) + Pnc * Natural Capital (NC)

(Don’t ask me about the Pmc, Phc, and Pnc, because I have no clue. Nor do I have any desire to have a clue.)

The math for calculating human capital is laid out also on page 30 of the 2012 report and is too long to include in this post, but here’s a taste of it:

. . . measuring the population’s educational attainment and the additional compensation over time of this training, which is assumed to be equivalent to the interest rate (8.5 percent in this case) . . .

and

The shadow price per unit of human capital is obtained by computing the present value of the labor compensation received by workers over an entire working life.

and

. . . for each nation we computed these shadow prices for every year within the 1990–2008 time period, and then used the average of this rental price of one unit of human capital over time as the representative weight . . .

It must be strange to be an economist. The people who made this report are focused on “social value” — attempting to make capitalism work for the health and well-being of our people and planet, by reducing said health and well-being to dollars and cents. I’m skeptical, but I’m glad at least that somebody is trying to account for the rapid depletion of our natural resources.

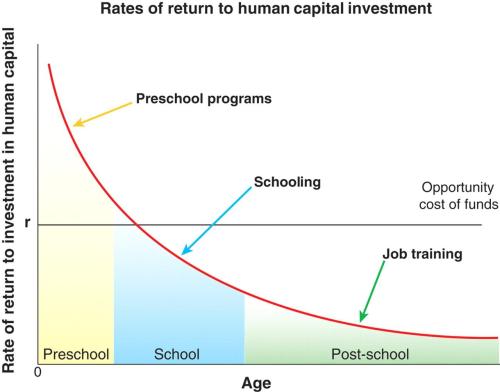

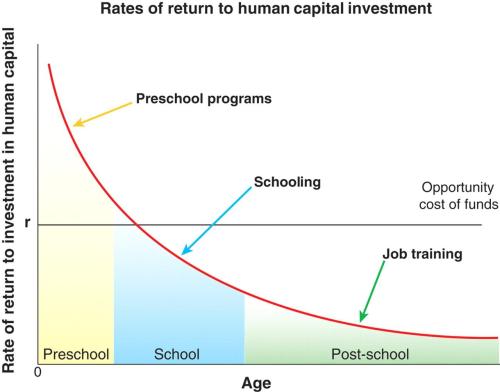

Anyway, back to what I said about somebody measuring the economic value of the unpaid work of mothering. That’s not exactly what they’re doing. They’re measuring the value of educating. Here’s a widely-used graph, from a Science Magazine article “Skill Formation and the Economics of Investing in Disadvantaged Children” by James D. Heckman (2006).

Source: Science Magazine

The article has a curious blind spot when it comes to the job of the earliest education, the contribution of the parents. A lot of studies focus on “disadvantaged children” and “children in developing countries.” Here’s a quote:

Research has documented the early (by ages 4 to 6) emergence and persistence of gaps in cognitive and noncognitive skills (3, 4). Environments that do not stimulate the young and fail to cultivate these skills at early ages place children at an early disadvantage. Disadvantage arises more from lack of cognitive and noncognitive stimulation given to young children than simply from the lack of financial resources.

The assumption here is that a normal environment, which somehow appears naturally and out of the blue, provides adequate stimulation to cultivate skills needed later in life. Actually, no. Somebody made it happen. A parent.

And it was a hell of a lot of work.

Here’s an estimate of the unpaid labor value of a mother’s work:

If paid, Stay at Home Moms would earn $134,121 annually (up from 2005’s salary of $131,471). Working Moms would earn $85,876 annually for the “mom job” portion of their work, in addition to their actual “work job” salary.

(From “What is Mom’s Job Worth,” by Salary.com.)

(Note: there’s a serious omission here. According to the Pew Research Center, the percentage of stay-at-home parents who are dads is up to 16%. I don’t know if anybody’s ever run the numbers for dads.)

Never mind the costs of raising a child. According to a recent report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which says that “a middle-income family with a child born in 2013 can expect to spend about $245,340 ($304,480 adjusted for projected inflation*) for food, housing, childcare and education, and other child-rearing expenses up to age 18. Costs associated with pregnancy or expenses occurred after age 18, such as higher education, are not included.”

By “middle-income family, they mean “the middle third of the income distribution for a two-parent family with children.” This is the “normal environment” referred to in Science Magazine, although the number of single-parent households in the U.S. has jumped from 19.5% to 29.5%.

And the annual income at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour is only $15,080.

On a family level, the economics of parenting just makes no sense. Wages are far too low to raise children.

It makes no sense on a societal level either. What happens, I wonder, if you take the cost of raising a child, plus the cost of a formal education, plus the unpaid labor of the parents, and compare it to that person’s “human capital” over a lifetime? You could calculate it. But honestly, I’m afraid to even try.

The problem here isn’t with the children. And it isn’t with the parents. It’s with the way we understand (or don’t) understand our own economy.

-END-