For whoever hasn’t been following this bit of news – it’s been in the national media – teachers in Seattle are boycotting a standardized test called Measures of Academic Progress, or MAP. The boycott was initiated by teachers at Garfield High School. Students there are on serious testing overload! There are a bazillion tests required for graduation, which is a problem in and of itself. And on top of that, there’s the MAP. This test is not required for graduation and students are not taking it seriously. At the same time, teachers evaluations are strongly affected by the student’s test results.

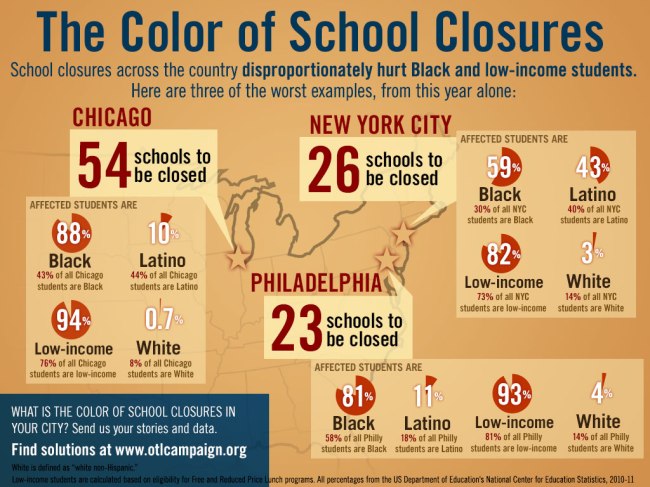

All these issues – testing overload, tests being used inappropriately – are a national problem. Some consider excessive testing to be child abuse. Testing is pushing out time for learning. Many people agree that basing teacher evaluations on student test scores is highly arbitrary. Parents are frustrated when standardized tests are used for student placement in lieu of the human judgment by teachers.

Something else is going on, too. Our schools are facing many different kinds of privatization, from privatization of schools (such as charter schools and vouchers) to privatization in schools (transforming schools in the model of the private sector, including dehumanized, centralized control). This is misleadingly called “education reform.” That’s where the push toward high-stakes testing is coming from. That’s why a lot of states have passed laws mandating that student test scores make up one-half of a teacher’s evaluation. And that’s why there’s a call for “multiple measures” of student achievement – that is, multiple tests. Test overload.

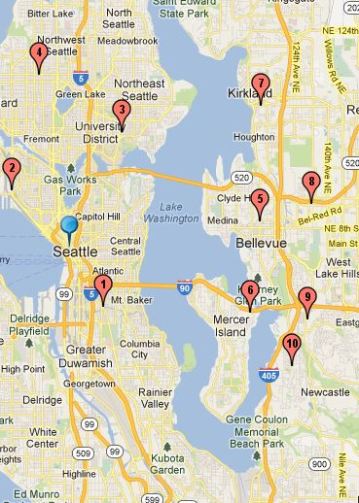

There’s pushback from the community affected. Students, parents, and teachers alike. At Garfield, all three have come together – the teachers are boycotting, the PTSA supports it, and the associated student body supports it. All over the city and nationally, people are supporting the boycott. By coming together, I think we could kill the MAP. It’ll be a major win not just for Garfield and not just for Seattle: it will provide inspiration nationwide.

But then what? This brings me to the rather inconvenient fact that most of us fighting this standardized testing overload seriously need to grapple with. Some parents, some teachers, and some students like the MAP. Some oppose it, some support it.

And to be honest, they do it for some good reasons. Kids fall through the cracks. They really do. Without testing, some struggling students are not identified and end up graduating high school without being able to read. Without testing, some advanced learners are not identified. The MAP test catches some of those. And in some cases, the MAP is the only tool that’s useful for that purpose.

But then on the other hand, the Seattle Public School District is using it to bar students from the advanced learning program. Kids who demonstrate the ability to work well above grade level, but who don’t meet a score cutoff on the MAP test, are denied access.

Parents do have a recourse, but it has the word “Privilege” smeared all over it. You can appeal. For an appeal to be successful, in many cases, that means private testing. Two groups of people can get that: the group of parents who can afford the $300 per child that you would need to slap down; and the group of parents whose kids qualify for free-or-reduced lunch AND who have the wherewithal to jump through all the hoops needed to locate and arrange private testing, get their child there on time and prepared, and appropriately fill out the forms. Plenty of kids are going to fall through the cracks.

Is it worth it? Is identifying some children’s education needs worth the price of barring others from programs they need?

And is it worth jeopardizing teachers’ jobs over an arbitrary measure?

And is it worth spending so much learning time and money and so many instructional resources (library space, tutor time, you name it)?

I don’t mean the answer is “no.” I mean that these are questions we need to be asking and answering as a community of students, teachers, and parents.

Also, we need to be asking these questions separately from and independent of the private sector individuals and organizations who are interested in privatizing schools. They want to know, “How can we transform education so it looks good to us?” But we want to know, “What’s the best way to bring up and educate our kids?”

We also need to be asking questions like, “How much testing is too much?” and “What kind of testing is appropriate for our kids and at what grade?” and “What is this test measuring?” and “What are the limitations of this test?”

(That last is a biggie. To understand what the limitations are, people need to understand some basic statistics concepts. Measurement error, confidence level, standard deviation. Almost nobody does. We’re using these numbers without understanding them. We’re worshipping the numbers.)

We need to be asking these questions.

Because even if the MAP goes away, it’s going to be replaced by something else. There will be a whole slew of new tests to measure mastery of the new Common Core Standards. (By the way, one organization that will be sitting pretty is Pearson, the company that makes tests and curriculum and as such, has a vested interest in promoting high-stakes testing and testing overload.) States will continue to pass laws mandating that student test results play a role in teacher evaluations. Communities will continue to resist.

So tell me, what do you think? How are these tests helpful? How are they harmful? Is there a way to use them without getting burned? Is there a way to stop using them without leaving some students’ needs unmet? Let me know what you think.