Sometimes I get a bug up my butt and can’t think about anything else until I have researched it to death. Especially if I’m angry. For the sake of my well-being and the rest of my life, I ought to stay off the Internet so I don’t see this kind of thing, but I saw it, so there we are. Nancy Mace, politician, explaining that she watches ICE videos for fun and can’t think of anything more “American” than the cruel and violent kidnapping of innocent people. What kind of person is that wrongheaded and horrible? Like, how did she get that way? It suggests that she was raised with one kind of thinking, one warped vision of America that is the exact opposite of mine. Her family, her community, her church, her business profits–everything around her. I’m sure she recited the pledge of allegiance, but also certain the words “liberty and justice for all” went over her head.

So, I researched her ancestry. I shouldn’t have bothered, because the information is out there, generations of military and “prominent family” going back to the civil war, with a decorated Confederate soldier or officer or some such, and slaveowning. Just search her name in connection with Confederate ancestry and you’ll find it for yourself. There’s an article about 100 political elites with such a history, and she’s in it.

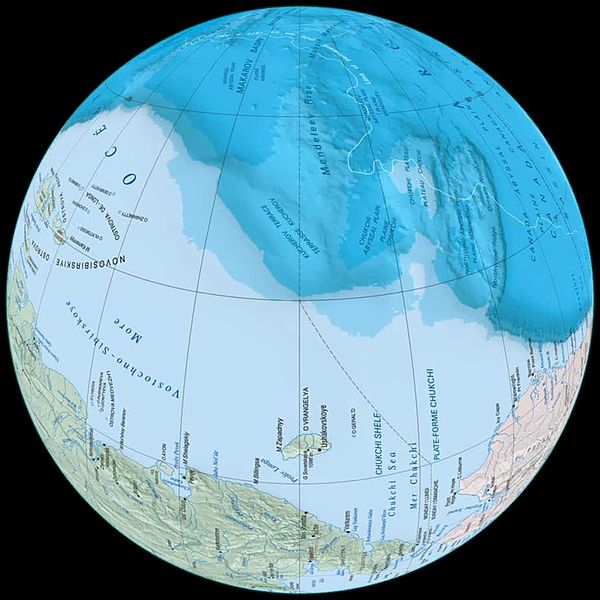

But no, I had to do the research the hard way. Her father, a brigadier, was easy. His parents, curiously, were not listed in any of the biographies I saw, and neither was his name or place of birth. His biography started when he graduated from a military school called the Citadel. That’s a time and a place, and the last name is common. After some thrashing about and chastising myself for wasting my time, I looked for people with that last name in the South around 1800 and eventually saw the link. Along the way, I saw lots of pictures of people who just looked friendly and respectable, ordinary except for the exclusion of people of color.

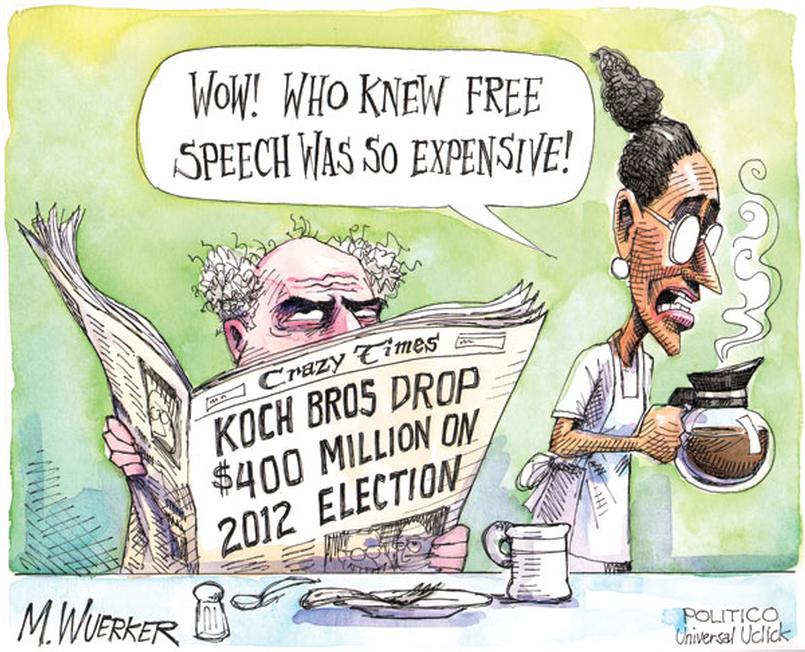

So what is this? This political moment? People are talking about fascism and comparing the administration to the nazis, and that’s not wrong, but it’s not right either.

What’s up with all the focus on Confederate statues and place names? Why has the January 6th coup attempt been glamorized?

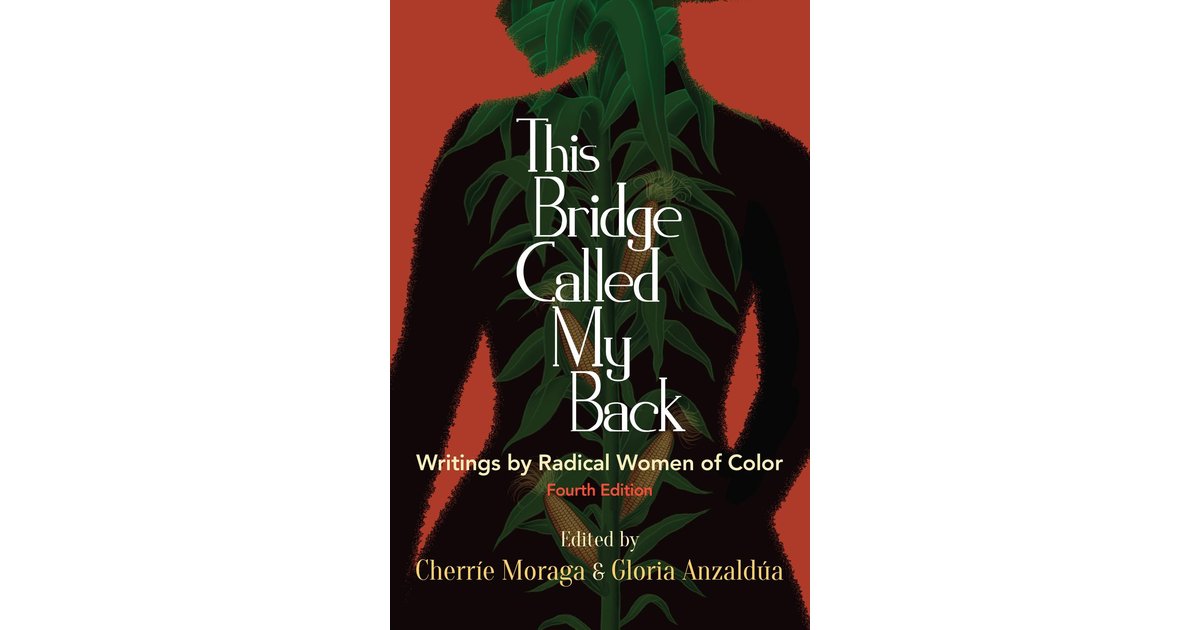

I mean, we all know, right? That the United States has a shameful history of kidnapping and enslavement of Black folks and massacre of indigenous folks. In my liberal education, I was taught that we were pretty much past it. Our nation became enlightened. White liberals figure we fought the confederacy and we won, and by the way we ended racism so we shouldn’t talk about it really.

I see signs here and there that say “Resist!” But they don’t say what to resist—what we are fighting against–or even what we are fighting for. (Liberty and justice for all.)

I propose that for today’s resistance (you know, whatever day you’re reading this), we resist the lies in our head, the ones that say, “After the midterms, everything will be okay. We’ll start going back to normal.” Normal wasn’t enough. This whole time that liberals were thinking normal was okay, and appeasing bigots, the descendants of slaveowners have been using their stolen wealth to bring back the confederacy, one piece at a time.

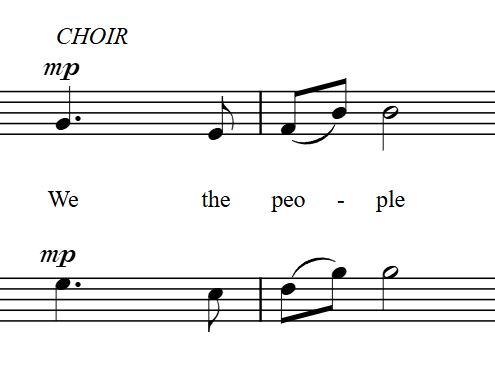

Well, we fought the confederacy once. But now we, the people, have to do it all over again.

Resist.