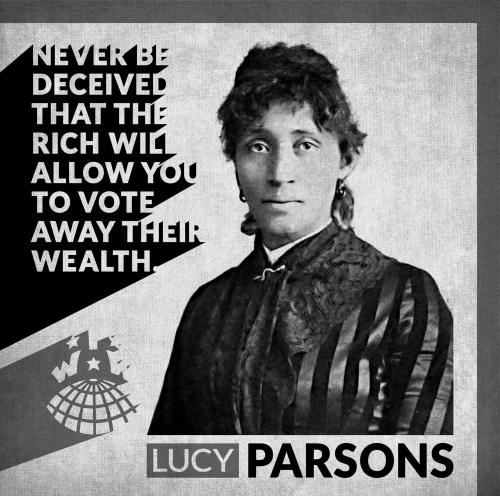

In honor of Juneteenth, I have a few remarks about Lucy Parsons — anarchist, revolutionary, orator, essayist, mother, seamstress. She became famous as a widow of a “Haymarket martyr,” anarchist Albert Parsons, and later for her own speeches and orations. The Chicago police called her “more dangerous than a thousand rioters” and, after her death, they disappeared all of the books and papers they could find.

Why was her speech so dangerous? She sought to liberate the downtrodden–or rather, she spent her life urging them to take direct action in liberating themselves.

In one of her more famous essays, “To Tramps,” she spoke to the 35,000 unemployed Chicago workers, who had been dying by starvation and exposure, and by throwing themselves into the river in despair.

stroll you down the avenues of the rich and look through the magnificent plate windows into their voluptuous homes, and here you will discover the very identical robbers who have despoiled you and yours. . .

Another of her better-known essays, “The Factory Child,” uses moving Victorian prose to decry the horrors of child labor.

O factory child! What can be said of thee, thou wee, wan thing? ‘Tis thy teardrop which flashes from the jeweled hand of the factory lord. ‘Tis thy blood which colors the rubies worn in his gorgeous drawing room. . . .

Some day . . . brave hearts and strong arms will annihilate the accursed system which binds you down to drudgery and death. Only then will the factory door to gender childhood be forever closed, and the schoolhouse be flung open, and all the avenues of art and learning be opened up to children of the producing many.

Another, less well-known essay is surprisingly relevant today. Her essay “Wage-Slaves vs. Corporations: What are You Going to Do About It?” takes aim at the funds spent by a life insurance company to influence elections. She writes:

Oh, I think I hear you say, “Why, I am going to use the ballot, the freeman’s weapon, and elect good men to office, who will seize the boa constrictor-like trusts and control them. Are we not free-born American citizens?”

Oh, are you though? Not too much assurance, please.

After explaining the political corruption, she asks:

What are you going to do about it?

Before Juneteenth, Lucy and her family had been enslaved by a doctor named Talliafero, who had moved the family to Texas in an effort to keep them enslaved. After the Civil War ended, Lucy’s family moved to Waco, Texas, where she secured her formal education in the first school for Black children.

Freedom after the Civil War was precarious. The countryside was full of white vigilante violence, Ku Klux Klan atrocities, kidnappings, and efforts to press freed Blacks into involuntary apprenticeships. At the same time, though, freedom must have seemed just over the horizon. Black people got the vote, and in places they were the majority, elected Black politicians. Globally, too, 1867-1871 was the time of Marx’s Capital and the Paris Commune. Lucy met Albert Parsons, a white man and former Confederate soldier, and they got married.

Then the door slammed shut for the couple. Neo-confederates came into power in Texas and outlawed interracial marriage. In 1873, Lucy and Albert fled to Chicago, where they became socialists, anarchists, and communists. Lucy worked as a seamstress and began publishing her work.

In 1877, the same year Reconstruction ended, railroad workers across the United States struck over a series of wage cuts that stole half their income and left them starving and desperate. Police, business owners, deputized militias, and the federal government banded together to break the strike. Rutherford Hayes, the Republican president, called in the National Guard for the first time the U.S. military had been deployed against strikers. Business owners and newspapers called for strikers to be poisoned, hanged, and shot. Dozens of Chicago workers were killed. Lucy’s husband responded with incendiary speeches of his own, and the local police advised him to leave town, on threat of murder.

All these experiences built into Lucy Parsons’ political analysis. Along with many other socialists of the time, she saw commonalities between chattel slavery and wage slavery, and between slaveowners and industrialists. She had seen the emancipation of enslaved people by military might, and then she had seen the failure of the ballot box to preserve liberty. She had seen extreme violence used to repress freedpeople and strikers.

And so began her lifelong project of emancipation.

Read more:

Lucy Parsons, An American Revolutionary by Carolyn Ashbough

Lucy Parsons Freedom Equality & Solidarity Writings & Speeches, 1878-1937, ed. Gale Ahrens

Goddess of Anarchy by Jacqueline Jones